Balancing Act.

DESIGN BITE

Due to its age and history, Europe allows visitors to look back in time. I looked back in design.

Here is what I saw:

Intricate patterns, carvings, and sculptures. Simple technologies. Everywhere.

1300s AD. Upper half of a door and molding in The Alhambra, Granada, Spain.

1700s AD. Books on display in La Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain.

1452 AD. Chair at the head of a dining table in the Château de Gruyéres, Gruyere, Switzerland.

203 AD. Underside of the Arch of Septimus Severus, Roman Forum, Rome, Italy.

1500s AD. Sunlight streaming into nave of St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City, Italy.

400s BC. Fallen piece of column from the Parthenon at the Acropolis, Athens, Greece.

Time and time again, I stood in wonder at the levels of detail that were imagined and executed so, so many years ago.

Through modern art museums, articles, and window shopping, I look into the future of design:

Clean lines, sleek shapes. Advancing technology. Everywhere.

Stools (grey) disappear into table top when not in use and are replaced with bowls (white) for meals. Displayed in Musée Disseny, Barcelona, Spain.

This Giorgetto Giugiaro designed concept car greets visitors to the Nazionale dell'Automobile in Turin, Italy.

Watches epitomize simple design while using an unconventional material, wood. Sold in a random shop in Zürich, Switzerland.

I noticed an inverse trend between the increasing complexity of the function of objects and the decreasing complexity of ther visual forms.

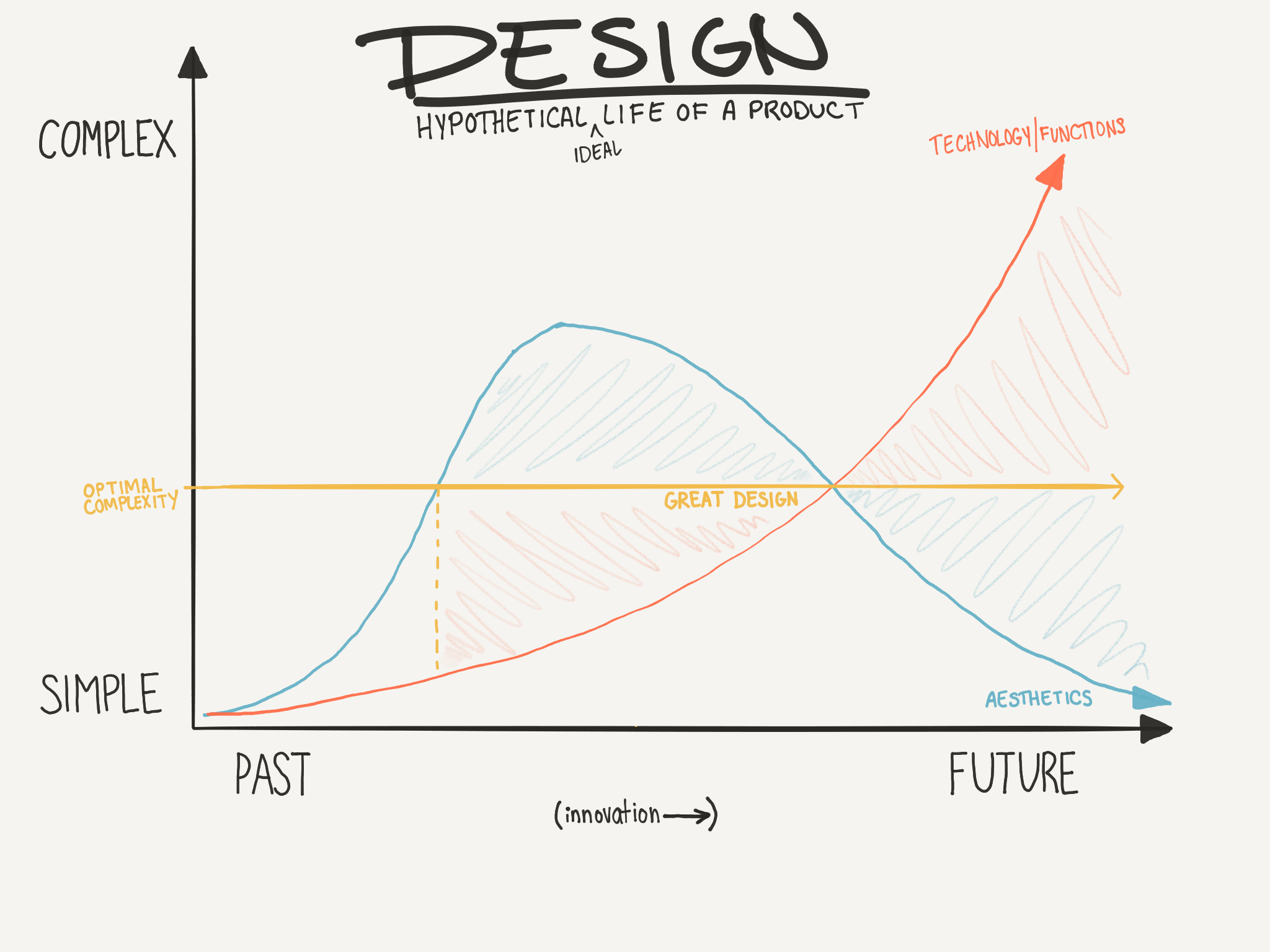

My math-loving brain developed a graph.

The ideal design lifecycle of a product might look something like this. I think some products do fit this generic mapping, with fluctuations along the way, but other products take on other shapes.

Say this graph demonstrates the life of the telephone: It began with an invention. In it's toddler stage, we saw rotary dial phones, phone booths, car phones. Each with relatively simple forms and simple functions. Through adolescence, we saw flip phones and BlackBerries®. Both form and function becoming more complex. And now, in adulthood, we see smart phones. Apple Inc. has been the pioneer in simplifying aesthetic forms while ramping up functional capacity.

I hypothesize that our brains enjoy a certain level of complexity, or stimulation, from the objects we interact with. Too much complexity stresses us out, but too little bores us. We seek just the right amount. And that amount indicates what we consider great design. When the balance is thrown too far off for too long, it is time to scrap innovation and turn to invention.

Often people expect innovation when a product suffers from bad design, but the answer may instead lie in invention. Henry Ford once said, "If I had asked the people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses."

1916 Ford Model T in Museo Nazionalle Dell'Automobile, Turin, Italy.